The most notorious and best remembered of all [the gales on the Yorkshire coast] was undoubtedly that of 10 February 1871 when a hundred ships were wrecked on the coast, including thirty in Bridlington Bay where an estimated seventy lives were lost. The winter of 1870-71 had been particularly bad, and a vast fleet of colliers had sheltered in the Tyne waiting for a break in the weather. Their chance came on 9 February when approximately 400 vessels made sail, many of them bound for Paris which was under German siege at this time. As the fleet reached Bridlington Bay the breeze died away and many of the vessels anchored offshore to await a favourable wind. However, it never came; a south-easterly gale accompanied by heavy sleet and snow sprang up early on the morning of 10 February. The local rocket apparatus, and Bridlington's two lifeboats, waited in readiness for the inevitable disasters.

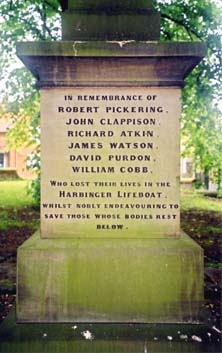

At 10a.m. five vessels ran for the beach to avoid sinking at anchor, and all struck near the Spa, south of the harbour, where the crews were saved by the lifeboats. One of the lifeboats, the R.N.L.1. Robert Whit worth , was taken out of service at this point. It was a heavy and cumbersome boat, and the crew had to be lifted from their seats as they were so exhausted from their exertions. The smaller lifeboat Harbinger was more easily handled, and she continued to attempt her almost impossible task. The brig Delta was seen south of the town in dire trouble; four of her crew had drowned while attempting to launch their own boat, and the Harbinger sped to rescue the captain who could be seen in the rigging. As she neared the wreck, a huge wave engulfed both vessels. When the boiling surf fell away, it was seen that the Harbinger had capsized, her crew were scattered and the man in the rigging had disappeared. Six of the nine lifeboat crew were lost; the remainder righted the Harbinger and were able to save themselves. The Delta was a 226 ton brig, built at Sunderland in 1839 and owned by T. Forrest of Whitby.

…

The following morning piles of debris littered the beach for several miles, and in some places the timber was piled eight or nine feet high. The death roll could not be accurately ascertained even at the time, but the most widely quoted figure was no less than seventy lives lost. Many of the victims were buried in a mass grave at Bridlington where a service has been held every year since that time. Even today, more than a hundred years later, Bridlington seafaring men remember stories of that awful storm, and the part their forbears played in the rescue.

…

Samuel Plimsoll, who was at this time campaigning for safety regulations for the protection of seamen, used the 1871 disaster at Bridlington as evidence for the great need to control safety in ships.

|